by Sean Fitzpatrick

Reverend Father, Esteemed Faculty, Good Parents, Honored Guests, Dear Alumni, Students:

Thank you for coming to our graduation of these seniors. Though I am grateful, truly grateful, for your traveling here, for your presence, for your support, I am sorry to say that this address is not exactly for you. It isn’t. Seniors, it is for you. It is, and this is it. This is our last Captains’ Table. But now, since the rest of you don’t seem too deterred that this address isn’t for you, and don’t seem to be going anywhere, I am happy to have you listen in if you wish, but I’d better tell you what Captains’ Table is first.

Captains’ Table was a new class at Gregory the Great Academy this year, and it involved me talking to, with, and sometimes at the seniors, these seniors. It was a time to talk shop, to tell stories, to study the art of leadership, to consider how things were with the younger boys, to give advice, never to complain, and to foster friendship. It was called Captains’ Table, with the word “Captains’” as a plural possessive, not a singular possessive—for the seniors are our captains. We adopt this title after the custom of Andre Charlier, the headmaster of a Catholic boarding school in France in the 1940s. Under the guidance of the dormfathers, the seniors at Gregory the Great Academy read letters written by Andre Charlier to the older students in his school, whom he called “captains.” The “Letters to the Captains” teach virtue, wisdom, the art of kindness, and a manliness that follow an ideal captured well by a real man-o-war captain, Frederick Marryat, who wrote “the greatest charm attached to power is to be able to make so many people happy.”

Now, when we started Captains’ Table this year, I quickly noted that this was to be a time when the seniors would gather round me and ask what they should, or could, do. The scenario reminded me immediately of a story I like very much: The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin by Beatrix Potter. Do you all know this story? I am not one to ask an audience to raise their hands, for it is humiliating for everyone. So, in the interests of sparing good folks from humiliation, here, very briefly, is the story for those of you who are unfamiliar with Nutkin.

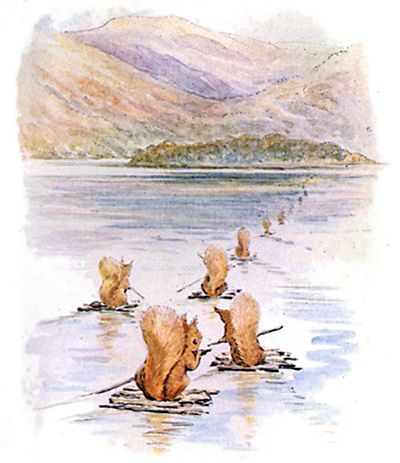

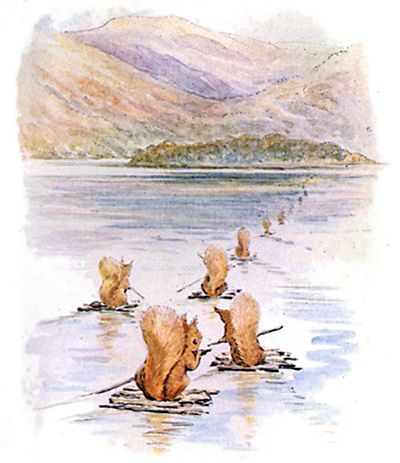

By a wooded lakeside, a band of squirrels build little rafts and punt out across the water to Owl Island, bringing empty sacks and three dead mice. Upon arrival, the squirrels process to a hollow oak tree where an owl called Old Brown lives. Laying the mice on his doorstep as an offering, the squirrels bow reverently, begging Mr. Brown to favor them with permission to gather nuts on his island. But one squirrel, Nutkin by name, disregards these respectful rituals, and bobs impertinently before the impassive owl, singing riddling tunes very obnoxiously. Old Mr. Brown pays Nutkin no heed, taking the mice without a word, allowing the squirrels to fill their sacks with nuts. For the next week, the squirrels return every morning bearing a new gift for Old Brown, and every morning Nutkin taunts the owl with riddles and rhymes. Mr. Brown tolerates Nutkin’s impudence imperviously, allowing the squirrels to labor, while the naughty Nutkin plays alone and does no work. On the last day, Nutkin’s cheekiness creates a crisis, after which he finds himself in the waistcoat pocket of Old Brown—that is to say, in his talons. He drags Nutkin into his house, but the rebel escapes by tearing his tail in two and fleeing, never to chatter another rhyme again.

Now, I drew a connection between The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin and Captains’ Table because I thought of the seniors as squirrels gathering around me, Old Brown in this case, to converse and confer before striking out upon their duties. So, seeing this obvious similarity, I quickly established the necessary rubrics, demanding that the seniors bring me some appetizing offering at the beginning of every Captains’ Table. It was a good idea. But it didn’t quite turn out. You see, the squirrels brought Old Mr. Brown things that he liked, presumably: dead mice, a dead mole, dead fish, dead beetles, some honey—it was a little strange when they brought him an egg—but the point is it all seemed fitting fare for an owl. What these squirrels brought was not fitting fare for this owl. Without meaning to cause offense, they brought me junk—for the most part. There was, I think, one time with some nice cheese and maybe some fruit, and a couple good cups of coffee, but I have never choked down so many Skittles and Poptarts and chippy-snackies and hot-liquid-sugar since I don’t know when. I realize it was all top-shelf merchandise from the black-market these guys run in the dorms, and I thank you, seniors, for dipping into your goods for me, but it was… I tried to be polite and ate it all up as best as I could, especially since there was always so much care and pride taken in the presentation of these gifts. Eventually I had to pass it round the table. It was just too much. You never seemed to be too offended by sharing.

Now, I drew a connection between The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin and Captains’ Table because I thought of the seniors as squirrels gathering around me, Old Brown in this case, to converse and confer before striking out upon their duties. So, seeing this obvious similarity, I quickly established the necessary rubrics, demanding that the seniors bring me some appetizing offering at the beginning of every Captains’ Table. It was a good idea. But it didn’t quite turn out. You see, the squirrels brought Old Mr. Brown things that he liked, presumably: dead mice, a dead mole, dead fish, dead beetles, some honey—it was a little strange when they brought him an egg—but the point is it all seemed fitting fare for an owl. What these squirrels brought was not fitting fare for this owl. Without meaning to cause offense, they brought me junk—for the most part. There was, I think, one time with some nice cheese and maybe some fruit, and a couple good cups of coffee, but I have never choked down so many Skittles and Poptarts and chippy-snackies and hot-liquid-sugar since I don’t know when. I realize it was all top-shelf merchandise from the black-market these guys run in the dorms, and I thank you, seniors, for dipping into your goods for me, but it was… I tried to be polite and ate it all up as best as I could, especially since there was always so much care and pride taken in the presentation of these gifts. Eventually I had to pass it round the table. It was just too much. You never seemed to be too offended by sharing.

I apologize if that is all news to you. Despite all the candy, I will think fondly upon my first year of Captains’ Table, and the Nutkinish impression you all made upon me. Remember I read The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin aloud to you, and it was Eddie Fay who illuminated one of the darkest corners of my mind when he solved the mystery of Nutkin’s italics right before my eyes. For that, Mr. Fay, I will be grateful to you for as long as I live. And I hope you all will remember Nutkin, if not as long as you live, at least for a few years of life after the life you have lived here with us at St. Gregory’s—because you all stand on the brink of the risk of becoming Nutkin yourselves. Nutkin’s tale is a tale for you, seniors, and that for many good reasons. Even squirrels are important in the ways of the world. As Thoreau quipped, “The squirrel that you kill in jest, dies in earnest.” The balance between sanity and insanity is determined not only by the lively, but also by how they live their lives. Will they be lively with purpose or without purpose? Captains, squirrels, do you set sail from here with purpose, or without purpose?

Now, seniors, I remind you that I am a graduate of St. Gregory’s myself. Not only that, I have seen a great many seniors graduate from St. Gregory’s. And I will tell you this—something that has not, to my knowledge, been told to any senior class before yours: there are similarities to Nutkin in all of you: things that you must reverence and restrain. Things you must be glad of, and be wary of. The education at St. Gregory’s is dangerous, and that is precisely why it is worthwhile. The world exults in the average and the tolerant. Reject these, seniors. In the words of Charles Dickens’ Ghost, “Slander those who tell it ye. Admit it for your factious purposes, and make it worse.” Troll fearlessly the ancient yuletide carol, seniors. We at St. Gregory’s desire to mount the naked height of poetry, which is God’s holy mountain. We at St. Gregory’s long to fly higher, even if we risk the flight of Icarus. It is good to be close to the gods.

As a result of this spirit, however, St. Gregory’s graduates often march their way out of high school and into the real world, only to find it not as real as the world they have known. And they do not always fit in, or make good decisions in trying to re-establish the joy of their youth. There is a tendency and a tradition of adding a compensating swagger to their step which is not in keeping with the humility of our holy patron. Seniors, be responsible in wielding your weapons of mirth. As a corps of comrades, you may make a mark that is considered by a fragmented world as dangerous, borne aloft as it is on the strange wings of poetry and music—wings that are considered dangerous because they are good, true, and beautiful—but, dangerous as such—wings that are so dangerous, the serious young men of today no longer learn how to manage them with any seriousness, for they are too serious to be bothered with Bacchus. I quote Robert Louis Stevenson’s introductory verse to Treasure Island to illustrate the youths I refer to:

If sailor tales to sailor tunes,

Storm and adventure, heat and cold,

If schooners, islands, and maroons,

And buccaneers, and buried gold,

And all the old romance, retold

Exactly in the ancient way,

Can please, as me they pleased of old,

The wiser youngsters of today:

— So be it, and fall on! If not,

If studious youth no longer crave,

His ancient appetites forgot,

Kingston, or Ballantyne the brave,

Or Cooper of the wood and wave:

So be it, also! And may I

And all my pirates share the grave

Where these and their creations lie!

Which side of the grave do you choose? The graduates of St. Gregory’s are not so wiser, not so studious, that they no longer crave the ancient appetites of the old romance. God forbid and God be praised. And they show it in reels, rhymes, and even rogueries with a will that has made for us a reputation that I, for the most part, gladly accept—though it is sometimes a hard reputation. Seniors, be responsible. The life we are arming you with is something that can, and should, be risky. As you all know by now, there is nothing that we consider worth doing at St. Gregory’s that can be called safe. That is the way of the weak. We hold that, if there are no obstacles to be overcome, what victory can be had? Nothing—for nothing worth doing is free of peril. There is always a little victory, a little satisfaction, in every rebellion. But pause for a moment.

Graham Greene called The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin “an unsatisfactory book,” and it deserves this designation only insofar as it does not satisfy the accepted formula of the nursery morality tale. A little perversity is always satisfactory. The Bohemian life of leisure that dangles its legs above the law in a realm of music and poetry often carries with it an impudence that is almost an innocence in its scorn for societal norms. Nutkin’s is the attitude that does not succumb to formalities. Nutkin is the ancestor of Ratatösk, the ancient Squirrel of Mischief, who runs up and down Yggdrasil, the Tree of trees, making trouble between the eagle that nests in the branches high above and the dragon that gnaws at the roots deep below. The squirrel tells the dragon how the eagle plans to destroy the dragon; then he goes to tell the eagle how the dragon plots to devour the eagle. (“What do they teach them at this school?” There’s nothing like a little pagan myth to expand a Christian worldview.) The irresistible agent of insubordination that launches itself against the rigid systems of the world is the struggle between the playful and the pragmatic, between Tom Sawyer and Aunt Polly, between the wild and the wise.

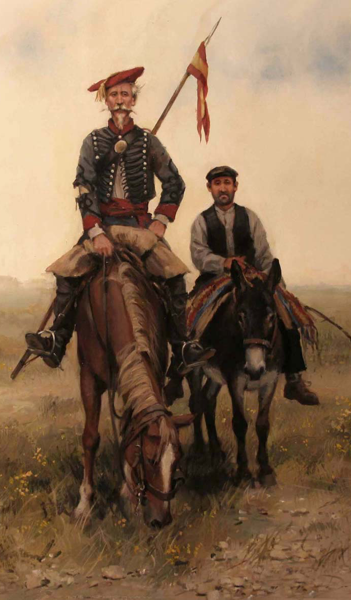

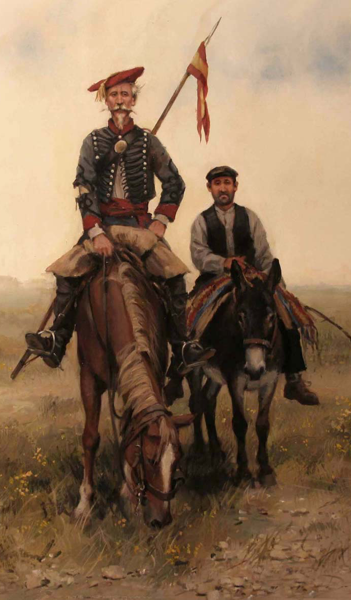

Rebels you should be, boys, for you should be boys—minstrel boys. Take up the sword of your fathers and the harps of your forefathers. Do not cease to sing the songs of your land of song. Rebels you must be, like William Wallace and the Highlanders; but rebels like Nutkin are not dangerous enough for any rebel worth his salt, for Nutkin is a rebel without a cause. The romance of rebellion has a high cause and it requires suffering and sacrifice. Though you should sing Nutkin’s songs—and please do—do not become Nutkin. Take Nutkin’s poetry to heart, but not his impertinence. Take on his liveliness, but not his laziness. Take song and poetry on the road with you, but do not be rude along the way. There is a book about the road that lies before you: the road of life; or as Chesterton called it, “a straggling road in Spain, up which a lean and foolish knight forever rides in vain.” The Adventures of Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes is a roadmap that can bring the peace of divine madness to those tempted to surrender to worldly sanity, for in the wise words of the ass-headed Bottom, “Reason and love keep little company together nowadays.”

To those who have not read Don Quixote yet, it goes like this. Having lost his reason reading books of chivalry, Don Quixote dons armor, mounts his nag, Rocinante, and sallies forth on the dusty plains of Castile with his squire, Sancho Panza, to pursue all that he has perused, to live what he has loved. He rides in search of a glorious world as he upholds a forgotten code of honor, bravery, justice, and nobility, dedicating his heroic deeds to his imagined lady, Dulcinea del Toboso. Beyond his village, the self-proclaimed knight errant trots and trips headlong into Renaissance Spain with paradoxical delusions that try to resurrect a dead world. The result is a colossal confusion of logic and folly, of reason and madness, of laughter and tears. Flying wildly with horse, lance, and squire, Don Quixote takes the road seeking knights, wizards, ladies, kings, and castles. But the road carries him to hard knocks and harder realities. Don Quixote only encounters rogues, goatherds, convicts, chambermaids, and inns. Again and again, his imaginings are denied. His manners are ridiculed. His purposes are foiled. The Knight of la Mancha, the Knight of the Sorrowful Face, is beaten, buffeted, bruised, and broken at every turning. But Don Quixote is resilient. He continues to see giants where there are only windmills, and to challenge and charge them despite falls and despite scorn. He sees what he has trained himself to see. What Don Quixote brings to the Modern Age after failing to find the Middle Ages is an Age of Faith.

The quest of Don Quixote is the quest of every Christian soul: to bring harmony and order to times that are out of joint. What Don Quixote finds is that the world is sundered and senseless, and the work to rebuild among the ruins is treacherous. Though he is trampled and trounced time and again, Don Quixote resolutely rides on for the unity and wisdom of bygone days and is upheld by his vision as he battles through the divisions and disconnections of modernity. There is a wisdom that belongs to idiots. Truth can be elusive—even illusory. “The foolishness of God is wiser than men,” writes St. Paul. Don Quixote may be mad, but there are forms of madness that are divine. Don Quixote may see things that are not visible, but only because he looks beyond the veil. The world is not broken. The pessimism that fragments reality is a falsehood. The world is not divided, but unified. Don Quixote is a hero of the indomitable power of Christian optimism, Christian imagination, and the glorious Christian folly that perceives the highest realities in the lowliest realities. Don Quixote is an icon of the chivalric Christian warrior because he has dreams that are out of reach, but he believes in them still. He is a man of great faith. It is only when the illusion is lost, when sanity shakes off insanity, when reveries are replaced with realities, that Don Quixote is truly conquered. Dostoevsky wrote in his diary that Don Quixote was “the saddest book ever written,” because “it is a story of disillusionment.” If the logic of the world is all there is, what reason is there to be sane? Reality must be touched by the imagination if men are to escape from the madness of reason alone.

The quest of Don Quixote is the quest of every Christian soul: to bring harmony and order to times that are out of joint. What Don Quixote finds is that the world is sundered and senseless, and the work to rebuild among the ruins is treacherous. Though he is trampled and trounced time and again, Don Quixote resolutely rides on for the unity and wisdom of bygone days and is upheld by his vision as he battles through the divisions and disconnections of modernity. There is a wisdom that belongs to idiots. Truth can be elusive—even illusory. “The foolishness of God is wiser than men,” writes St. Paul. Don Quixote may be mad, but there are forms of madness that are divine. Don Quixote may see things that are not visible, but only because he looks beyond the veil. The world is not broken. The pessimism that fragments reality is a falsehood. The world is not divided, but unified. Don Quixote is a hero of the indomitable power of Christian optimism, Christian imagination, and the glorious Christian folly that perceives the highest realities in the lowliest realities. Don Quixote is an icon of the chivalric Christian warrior because he has dreams that are out of reach, but he believes in them still. He is a man of great faith. It is only when the illusion is lost, when sanity shakes off insanity, when reveries are replaced with realities, that Don Quixote is truly conquered. Dostoevsky wrote in his diary that Don Quixote was “the saddest book ever written,” because “it is a story of disillusionment.” If the logic of the world is all there is, what reason is there to be sane? Reality must be touched by the imagination if men are to escape from the madness of reason alone.

Though lengthy and repetitive, those who can keep getting up, galloping, and falling again with Don Quixote page after page will build the resolve to do the same in their own lives day after day. The adventures of Don Quixote are a Passion where the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak. The novel takes up its cross, chapter after chapter, and follows after Christ. Chapter after chapter, the Knight of the Sorrowful Face falls, and, chapter after chapter, he gets up again and carries on—or, I should say, carries it on. It is a book that plays out with all the pain and poignancy, all the humanity and humor, that composes the chivalric call of the Christian life. “The Camino Real of Christ is a chivalric way,” writes John Senior, “romantic, full of fire and passion, riding on the pure, high-spirited horses of the self with their glad, high-stepping knees and flaring nostrils, and us with jingling spurs and the cry “Mon joie!”—the battle cry of Roland and Olivier. Our Church is the Church of the Passion.”

Though knighthood is extinct, that is no reason why chivalry should be dead. Don Quixote’s anachronistic knighthood is a model for rejecting the world when the world is wrong. This course, this straggling road of sudden perils, is one where Catholics often feel broken, bruised, even beaten. But, like Don Quixote and Our Lord, all are called to pull themselves back up and carry on, to sally forth yet again undaunted by failure, beating down discouragement, and determined to be the enemy of evil. Catholics must learn to ride even if it be in vain; to tilt and be toppled; to be conquered for Christ and be called fools for His sake. Again, from St. Paul, “God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise, God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong, God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are.”

Considering Nutkin and knighthood side by side, the word “errant” suddenly becomes a double-entendre. The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin is a tale about the importance of order, the pleasure of disorder, and the need to balance the spirit of Pan with the spirit of Demeter. Seniors, take heed and take heart. The wild things of the world are a delight, but they cannot carry the day, as Aesop’s Grasshopper demonstrates. The waggish wiggle of Mother Goose’s tail-feathers and the sublime nonsense that dances like a sunbeam around the grave facts of life must find their place, their difficult balance. The jester must not overthrow the king. Be wary. Do not be rebels without a cause, for that would be an abuse of the gifts you have been given. But rebels you must be. The world is too far gone for anything less than rebellion. You know that the universe is a song and a riddle, and you know its refrains by heart. Sing loudly, but sing wisely, prudently, and modestly. You may otherwise end up in the waistcoat pocket of the world. Be demure in your delight. There is a difference between mischief and mayhem, and it is on this difference that Nutkin provides a winking word to the wise. Do not be foolish in your role of being fools for God.

It is never wrong to play the fool for the greater glory of God. Miguel de Cervantes learned this from Don John of Austria at the Battle of Lepanto, recognizing the heroism of one who ran the risk of ridicule to uphold the sacred things forgotten by modern man. Cervantes sensed a new breed of hero in the madcap Don John, a hero whose heroism was new because it insisted upon ancient truths spurned by the modern world. Cervantes saw in him the inspiration for Don Quixote, whose heroism rejoices in the words of the Crucified King, “If the world hate you, know ye, that it hath hated me before you.” Don Quixote is a book about Christian knighthood and the Christian condition: the need to charge on; to be seen and mocked as mad; to be a fool for a good cause; to do what heaven deems right even when the world calls it wrong; to be a defender; to be principled; to be brave; to be unwavering; to be conquered again and again and keep rising from the dust. Being “quixotic” does not mean being quaint or charming or naïve. It does mean being Nutkin. It means laboring onwards and suffering rejection while, at the same time, rejoicing in the joy of the journey, even if it is up a via dolorosa.

Seniors—Captains—at St. Gregory’s, you have found something good. You won’t necessarily find it out there. The odds are stacked against you. Never forget that there are tears in things. Prepare. Hold fast to the good you have found. Hold fast to it, even if it proves an illusion in the world you belong to, because it is the illusion of our school, of your school, because it is good. It is the illusion of reality—of a world worth living and dying for. Keep it alive. Live it. Live it wherever you are with a song and a poem, even when you fall or meet with scorn—especially when you fall or meet with scorn. To quote from Charlier, “Perceive slackness, vulgarity, and cheating, as if these were a curse. I want boys that are upright, that look you in the eye, and who speak firmly. I tell you again: be humble. Look for strength where it is: only the spiritual view can give it to you. And it will give to you the radiance that illuminates your souls and the desire to pass it to others.”

Seniors, I have never given you an assignment for Captains’ Table. For this, our last, I am. You have heard The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin. For your homework, read The Adventures of Don Quixote. There will be a test at some point—but I will not be the one to give it to you. It may be more a trial than a test. I pray that you pass it triumphantly with flying colors.

It is my honor to address you all today. For those of you who don’t know me, my name is David Hahn, and I am the son of the renowned writer and speaker, Kimberly Hahn.

It is my honor to address you all today. For those of you who don’t know me, my name is David Hahn, and I am the son of the renowned writer and speaker, Kimberly Hahn.

Now, I drew a connection between The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin and Captains’ Table because I thought of the seniors as squirrels gathering around me, Old Brown in this case, to converse and confer before striking out upon their duties. So, seeing this obvious similarity, I quickly established the necessary rubrics, demanding that the seniors bring me some appetizing offering at the beginning of every Captains’ Table. It was a good idea. But it didn’t quite turn out. You see, the squirrels brought Old Mr. Brown things that he liked, presumably: dead mice, a dead mole, dead fish, dead beetles, some honey—it was a little strange when they brought him an egg—but the point is it all seemed fitting fare for an owl. What these squirrels brought was not fitting fare for this owl. Without meaning to cause offense, they brought me junk—for the most part. There was, I think, one time with some nice cheese and maybe some fruit, and a couple good cups of coffee, but I have never choked down so many Skittles and Poptarts and chippy-snackies and hot-liquid-sugar since I don’t know when. I realize it was all top-shelf merchandise from the black-market these guys run in the dorms, and I thank you, seniors, for dipping into your goods for me, but it was… I tried to be polite and ate it all up as best as I could, especially since there was always so much care and pride taken in the presentation of these gifts. Eventually I had to pass it round the table. It was just too much. You never seemed to be too offended by sharing.

Now, I drew a connection between The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin and Captains’ Table because I thought of the seniors as squirrels gathering around me, Old Brown in this case, to converse and confer before striking out upon their duties. So, seeing this obvious similarity, I quickly established the necessary rubrics, demanding that the seniors bring me some appetizing offering at the beginning of every Captains’ Table. It was a good idea. But it didn’t quite turn out. You see, the squirrels brought Old Mr. Brown things that he liked, presumably: dead mice, a dead mole, dead fish, dead beetles, some honey—it was a little strange when they brought him an egg—but the point is it all seemed fitting fare for an owl. What these squirrels brought was not fitting fare for this owl. Without meaning to cause offense, they brought me junk—for the most part. There was, I think, one time with some nice cheese and maybe some fruit, and a couple good cups of coffee, but I have never choked down so many Skittles and Poptarts and chippy-snackies and hot-liquid-sugar since I don’t know when. I realize it was all top-shelf merchandise from the black-market these guys run in the dorms, and I thank you, seniors, for dipping into your goods for me, but it was… I tried to be polite and ate it all up as best as I could, especially since there was always so much care and pride taken in the presentation of these gifts. Eventually I had to pass it round the table. It was just too much. You never seemed to be too offended by sharing. The quest of Don Quixote is the quest of every Christian soul: to bring harmony and order to times that are out of joint. What Don Quixote finds is that the world is sundered and senseless, and the work to rebuild among the ruins is treacherous. Though he is trampled and trounced time and again, Don Quixote resolutely rides on for the unity and wisdom of bygone days and is upheld by his vision as he battles through the divisions and disconnections of modernity. There is a wisdom that belongs to idiots. Truth can be elusive—even illusory. “The foolishness of God is wiser than men,” writes St. Paul. Don Quixote may be mad, but there are forms of madness that are divine. Don Quixote may see things that are not visible, but only because he looks beyond the veil. The world is not broken. The pessimism that fragments reality is a falsehood. The world is not divided, but unified. Don Quixote is a hero of the indomitable power of Christian optimism, Christian imagination, and the glorious Christian folly that perceives the highest realities in the lowliest realities. Don Quixote is an icon of the chivalric Christian warrior because he has dreams that are out of reach, but he believes in them still. He is a man of great faith. It is only when the illusion is lost, when sanity shakes off insanity, when reveries are replaced with realities, that Don Quixote is truly conquered. Dostoevsky wrote in his diary that Don Quixote was “the saddest book ever written,” because “it is a story of disillusionment.” If the logic of the world is all there is, what reason is there to be sane? Reality must be touched by the imagination if men are to escape from the madness of reason alone.

The quest of Don Quixote is the quest of every Christian soul: to bring harmony and order to times that are out of joint. What Don Quixote finds is that the world is sundered and senseless, and the work to rebuild among the ruins is treacherous. Though he is trampled and trounced time and again, Don Quixote resolutely rides on for the unity and wisdom of bygone days and is upheld by his vision as he battles through the divisions and disconnections of modernity. There is a wisdom that belongs to idiots. Truth can be elusive—even illusory. “The foolishness of God is wiser than men,” writes St. Paul. Don Quixote may be mad, but there are forms of madness that are divine. Don Quixote may see things that are not visible, but only because he looks beyond the veil. The world is not broken. The pessimism that fragments reality is a falsehood. The world is not divided, but unified. Don Quixote is a hero of the indomitable power of Christian optimism, Christian imagination, and the glorious Christian folly that perceives the highest realities in the lowliest realities. Don Quixote is an icon of the chivalric Christian warrior because he has dreams that are out of reach, but he believes in them still. He is a man of great faith. It is only when the illusion is lost, when sanity shakes off insanity, when reveries are replaced with realities, that Don Quixote is truly conquered. Dostoevsky wrote in his diary that Don Quixote was “the saddest book ever written,” because “it is a story of disillusionment.” If the logic of the world is all there is, what reason is there to be sane? Reality must be touched by the imagination if men are to escape from the madness of reason alone.