“Et Verbum caro factum est.” This passage from St. John’s Gospel is considered so important that it is included in every single Mass prayed in the Extraordinary Form, and has been so for centuries. What strikes me particularly about this passage is that it can be translated either as “the Word was made flesh” or as “a word was made flesh.” Of course John intends to refer to Christ, but as Catholics, we do not understand Revelation in a purely univocal way. Mary’s Fiat to the angel is not confined to our Blessed Mother alone, but to every mother who willingly greets the mystery of conception. Melchisedech’s sacrifice of bread and wine also presages the sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood. St. Paul explicitly tells us that not only Christ underwent death and burial, but also that all Christians join Him in the sacrament of Baptism. Dogmas are not mere formulas but conceptions meant to take flesh in the everyday practice of our lives. Our devout words must be “born-out” as well as borne out in our actions. And our words are composed not only of form in meaning, but of “flesh” or matter in the very language we speak. Following these considerations, inspired by the great educator John Senior, I and the other teachers at Gregory the Great Academy seek to teach Latin not simply as a language to be learned, but a language in which to imitate great and holy men, and a language in which to pray with the whole Church.

Things can be considered “good” from three points of view: the useful, the moral, and the pleasant. In all three ways, the study of Latin can be considered “good.” Considering usefulness, Latin is directly or indirectly responsible for more than half of English words, and so the study of Latin increases vocabulary, bolsters SAT and ACT scores, and prepares for careers in the sciences, law, and medicine. Moreover, the process of learning any new language often improves students’ abilities in non-linguistic areas such as mathematics, and the special precision of Latin syntax is particularly useful to precise and clear thinking.

These mental habits gained from the study of Latin lead into consideration of its “moral good.” Studiousness and precision, besides being words derived from the Latin language, are also virtues. Moreover, the literature of the Latin language offers the student access to a treasure trove of the higher virtues of faith, hope, and love. The song of the Knights Templars walking towards probable death, “Crucem Sanctam,” expresses their belief in Christ’s victory over death and their hope of sharing in that victory. Thomas Aquinas’s beautiful “Tantum Ergo Sacramentum” and Bernard of Clairvaux’s “Jesu Dulcis Memoria” move the heart toward love of God.

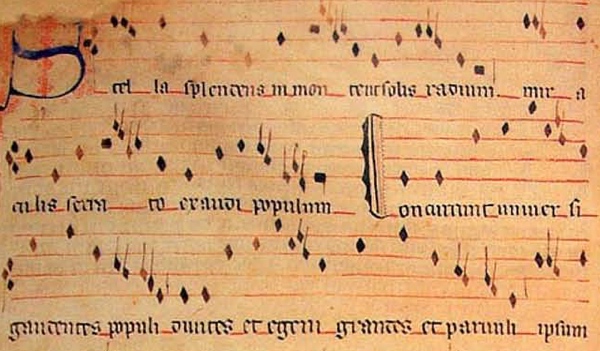

These hymns bring us to consideration of Latin as a pleasing language, both in the sense of being pleasing to the ears and the mind and as a language that aids us in experiencing the ultimate pleasure of communion with God. The historical development of the Roman liturgy illustrates both: what a feast for the senses a High Mass is, how each note of Gregorian chant accords with the language and the sentiment expressed by the language, and how all of these are centered on the real representation of the holiest moment in history! Moving on from the liturgy, we find Latin remaining the universal language of the universal Church when its head speaks in encyclicals and pastoral exhortations. The mystery of God’s Providence in His Son taking on the same flesh as sinful men is recapitulated in the mystery of placing His vicar in a particular location, and in the mystery of clothing this vicar’s voice in the flesh of Latin.

Rooted not only in the universal Church but in the Western tradition, Gregory the Great Academy seeks to flesh-out Latin. What does this look like? Instead of making the language mere grammar practice, we have our students memorize prayers and songs in Latin. In addition to vocabulary tests, we encourage our students to speak simple phrases and ask basic questions Latinly. As opposed to simply decoding texts by Latin authors, we encourage them to read the Latin directly for comprehension. As much as possible, Latin is not separated from the study of other subjects such as religion and history, but is joined to them, as students read the Latin Vulgate and read selections from the works of St. Augustine. And finally, Latin is present not as a class to be academically conquered, but as a mode of spiritual life. Outside the Mass, the best example is our praying of Compline, joining in the very same prayers prayed in the same language that millions of Christians through centuries have prayed. In this way Latin becomes an entry-way to both the democracy of the dead and the kingdom of heaven.