Can We Drop the Ascension Story?

by Sean Fitzpatrick

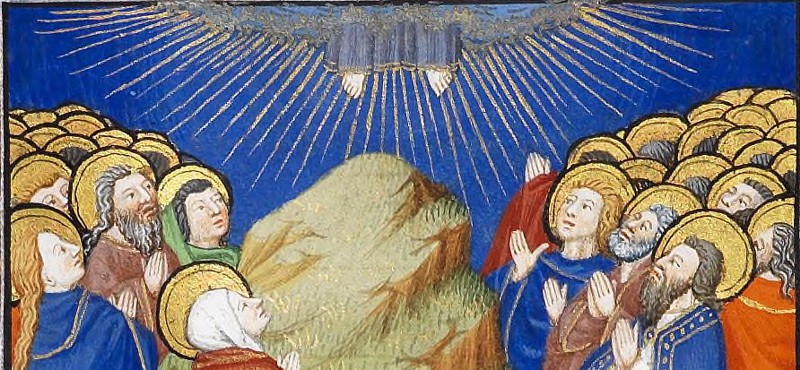

The Ascension of Jesus Christ, related in the Gospels of Mark and Luke and referred to throughout the New Testament, can be taken as something of an awkward anecdote. “And when he had said these things, as they were looking on, he was lifted up, and a cloud took him out of their sight,” (Acts 1:9). There is something about the Ascension that is inconceivable, even for a miracle—something that is almost too fabulous about the idea and image of Jesus “flying.” For those who stumble over the Ascension, there is often an aspect of mythical fantasy or primitive whimsy involved in accepting such a thing. Can people really take seriously the account of a Man floating into the clouds? Is the Ascension worth the risk of alienating those influenced by a cynical realism? This is the Faith, after all, not a fairy tale. Can we drop this story of Christ soaring through the sky?

C. S. Lewis takes on this very question in Miracles:

Can we then simply drop the Ascension story? The answer is that we can do so only if we regard the Resurrection appearances as those of a ghost or hallucination. For a phantom can just fade away; but an objective entity must go somewhere—something must happen to it. And if the Risen Body were not objective, then all of us (Christian or not) must invent some explanation for the disappearance of the corpse. And all Christians must explain why God sent or permitted a ‘vision’ or ‘ghost’ whose behaviour seems almost exclusively directed to convincing the disciples that it was not a vision or a ghost but a really corporeal being. If it were a vision then it was the most systematically deceptive and lying vision on record. But if it were real, then something happened to it after it ceased to appear. You cannot take away the Ascension without putting something else in its place.

Lewis draws attention to the physical importance of the Resurrection, pointing out that the Ascension, like the Resurrection, required a Body—a point that cannot be dropped. While the Ascension of Christ is a moment of spiritual transcendence that may be difficult to relate or react to, it is also a material mystery. In other words, the Ascension is as much about the body as it is about the soul. Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI wrote in Dogma and Preaching, “The expression of our belief that in Christ human nature, the humanity in which we all share, has entered into the inner life of God in a new and hitherto unheard-of way. It means that man has found an everlasting place in God.” The whole purpose of the miracle of the Ascension is that it points out the way for all flesh. It was a physical miracle involving a physical body that illustrated a relationship that is supernatural and eternal: “I am with you always, to the end of the age.”

The Ascension confirms and completes the Resurrection in a way that goes beyond mere symbolism. It has a tangible dimension as it deals with a tangible body. The body of Christ disappeared from the tomb and then reappeared before disappearing again forty days later. It did more than just vanish, however. It was moved. It went somewhere and, even now, is somewhere. It is this second disappearance that gives modern sensibilities some pause, for it is in a way stranger than the first. There is a kind of gravity in the idea of a man rising from the dead. There is a kind of levity in the idea of a man rising into the sky. That such spiritual physicality can arouse human incredulity and challenge the scientific thinker is precisely the point. Miracles are as factual and physical as they are spiritual, and their breaking with the bands of nature must be held as a matter of faith and as a matter of fact. G. K. Chesterton wrote in Orthodoxy:

I conclude that miracles do happen. I am forced to it by a conspiracy of facts: the fact that the men who encounter elves or angels are not the mystics and the morbid dreamers, but fishermen, farmers, and all men at once coarse and cautious; the fact that we all know men who testify to spiritualistic incidents but are not spiritualists, the fact that science itself admits such things more and more every day. Science will even admit the Ascension if you call it Levitation, and will very likely admit the Resurrection when it has thought of another word for it.

Chesterton agrees—the miracle of the Ascension cannot be simply dropped so long as man is material. The promise of extraordinary exaltation and supernatural splendor is not simply a matter of spiritual consequence, but a matter of physical consequence as well. Though Jesus’ body was glorified at the moment of the Resurrection beyond the normal experience of nature, He retained a body that was still in some veiled way like the body He had. There was certainly a different bodily relation that Jesus possessed with things like time and space, yet He was not outside of them. Though He did come and go at times like a specter, Jesus was sure to show His disciples that He was not spectral, as Lewis noted. He proffered His hands to His friends to touch and hold, for their eyes to see and believe. He ate and drank with them. He was flesh and blood. There was clear and careful intention in ascertaining these physical facts for the sake of the spiritual fact that was soon to follow.

![]() From Annunciation to Ascension, there is a concrete side to the Incarnation that is harder to accept than the mystical character of Our Lord’s miracles. As Our Lady showed, however, it requires faith to hold that with God nothing is impossible, even though some things might seem implausible. Though the modern mind may struggle to believe the story of a Man ascending into a heaven somewhere on high where, as the Son of God, He sits on a celestial seat at the right hand of God the Father, this is the challenge of reconciling faith with facts. The support of reason is present given the common sense involved in communicating a physical promise to physical creatures, but there must always be something obscure in the realm of faith.

From Annunciation to Ascension, there is a concrete side to the Incarnation that is harder to accept than the mystical character of Our Lord’s miracles. As Our Lady showed, however, it requires faith to hold that with God nothing is impossible, even though some things might seem implausible. Though the modern mind may struggle to believe the story of a Man ascending into a heaven somewhere on high where, as the Son of God, He sits on a celestial seat at the right hand of God the Father, this is the challenge of reconciling faith with facts. The support of reason is present given the common sense involved in communicating a physical promise to physical creatures, but there must always be something obscure in the realm of faith.

The Ascension of Jesus Christ is not simply a glorious finale of the story of human salvation, but a glorious beginning. In His departure from earth, Our Lord came to man as never before. By the mystery of the Ascension, Jesus gave his Church a miraculous sign that He is not far, and that the human body that houses the human spirit is something that belongs with God. As Pope St. Gregory the Great wrote concerning the significance of Our Lord’s bodily Ascension, “[Christ’s] intercession consists in this, that He perpetually exhibits himself before the eternal Father in the humanity which He had assumed for our salvation: and as long as He ceases not to offer Himself, He opens the way for our redemption into eternal life.”

Even though logicians (and theologians, for that matter) can demonstrate that heaven cannot be reached by a flight through the clouds, it does not render the Ascension account embarrassing or isolating. People need solid symbols and signs. They need to connect an ever-present, infinite God to the ever-present, infinite sky. The way of redemption exists for people living in the world, not for disembodied souls. It is outward yet inward, with defined margins and divine mysteries. Man requires bodily things to draw him to the divine. He needs incarnations just as he needed the Incarnation. The Word Made Flesh, therefore, operates in ways consistent with the principle of accord between the physical and spiritual, and this is the reason why we cannot simply drop the Ascension story.