Headmaster’s Address 2019 – by Luke Culley

Reverend Fathers, Faculty, Families, Students, Alumni, and Graduates:

Several months ago, in my senior Humanities class, one of these seniors asked me: “Why are we reading this stuff? It is all so unrealistic.” The stuff we were reading at the time was Beowulf. Beowulf is an Anglo Saxon epic about a warrior who, as a young man, comes to the aid of the Great people by fighting and killing the ogre-like Grendel, who feasts on human flesh. When Beowulf is an old man, he gives his life for his own people by fighting and killing a fire breathing dragon. Why do we read stuff like that? It is after all unrealistic, in that Grendel and the fire-breathing dragon never existed and, in my students’ estimation, never could exist. How is reading Beowulf different than playing dungeons and dragons? Maybe fun, but ultimately an irrelevant waste of time. Stuff and nonsense. But is it?

Before answering this question let us take a brief glance over some of the curriculum of Gregory the Great Academy to see what other stuff we serve up to our students throughout their time here. In literature class, the freshmen read about that merriest of all fighters – Robin Hood, who thought it great joy to get to know a stranger by challenging him to some cudgel play before allowing him to cross over a stream. The sophomores spend half of the year embroiled in the most famous battle of all time contemplating the godlike brooding mind of that greatest of all pagan heroes Achilles, – following in the bloody wake of Diomedes, Ajax, and Hector as they fight before the great city of Troy all for the sake of Helen – the most beautiful woman in the world. Juniors spend several months reading the Odyssey – the epic story about a man returning home to his kinsmen, his palace, and most importantly his wife, Penelope – a story that is full of fairytale-esque adventures with beautiful enchantresses, one-eyed giants, utopian dreamers, and drug addicts – a tale that culminates in a bloodbath where Odysseus joins forces with his son Telemachus and cleanses his own hall by fighting and killing all the men who have been loitering there for years despoiling his goods and his land, and dishonoring his wife and his family. It is a hard but happy ending. Seniors read the Aeneid, about the refugee from Troy, who must wander for years, denying himself the love of a beautiful and noble woman, before he reaches the far off ever-receding land the gods are calling him to. Upon arriving, he must fight (for six long and bloody books) many battles against terrible foes in order to gain a foothold and found his city. They read The Song of Roland that sings of a fierce laughing knight who is more valiant than he is wise, who holds his life like a plaything, and slays Saracens for pleasure and for the love of God and his emperor Charlemagne. It’s all pretty good stuff. And though these tales are not realistic, they are rooted in reality.

You may have noticed a common theme here: we read a lot of books about men fighting one another. Men who fight monsters, men who fight for a beautiful woman, men who fight to get home and then restore order in their home, men who fight for God, and men who fight for the fun of it? So why is that?

Could it be that to be a man one must learn to fight? And that fighting is one of the chief virtues of a man? I dare say that it is, and it is a virtue that is sorely needed especially by Christian men today. That is a reality, a hard and harsh reality. And sometimes the unrealistic (or poetic) is the best vehicle to bring us to the truth and the goodness and even the beauty of such hard realities.

Teach my hands for war and my fingers for battle. Sings David the giant-slaying shepherd-turned-king, whom God called “close to my own heart.” If David is close to God’s own heart then is God a warrior, and a trainer of warriors? How can this be? What sort of warrior and what sort of war are we talking about here? Maybe a priest can tell us.

A priest from the Saint Elijah Congregation visited our school only a few weeks ago and when he visited my classroom, he was taken by a sketch from one of the seniors behind me today of a crusader knight holding up the bloody head of a defeated Saracen. His face lit up with joy and he said, “This is great. It is so good you allow them to read stories about the crusades and encourage them to make these kinds of pictures.” Not what you might expect from a priest of God. Fr. Highton, our visitor, is the head of an order that is devoted to preaching the Gospel to the tribes and peoples who have never heard the Gospel before. He has missions in India, in Laos, and in Africa – and was, in fact, coming to our school not only to model his school in the Himalayan Mountains after our own but also to encourage our young men to come and join him in the missionary field. He told our students that every priest in his order takes a 4th vow – a vow of parrhesia. Parrhesia was the virtue most prized by the ancient Greeks: roughly it translates to courage in speaking the fullness of the truth. Their vow is to speak the truth God prompts in their hearts no matter what the consequences, “even if they cut us to pieces,” were his exact words.

A student asked Fr. Highton if his work was dangerous and difficult. He replied: “It’s not a picnic. Do not expect to come to a circle of ladies drinking afternoon tea. Every day is difficult and an adventure. When I wake up in the morning, I have no idea what the day will bring.” He made it clear that to engage in this work, one must have the heart of a warrior and told the class about a book that he considered seminal to his effort as a missionary: it is called The Christian Duty to Fight by Antonio Caponetto. He ended his talk by saying that “all men are not called to be missionaries in the way that God has called him, but that all men are required to be “epic.” There is a secret hidden in each one of us that only God can bring forth and that secret is the heroic path God calls us to.”

And sometimes that call might seem to demand unrealistic things, as Fr. Highton well knows, but the (seemingly) unrealistic should never deter us from following God’s commands. We must strive to be like Saint Peter and dare to walk on water, knowing that God rejoices in the unrealistic—or more precisely, he rejoices in overcoming everything that restricts our entering into the really real.

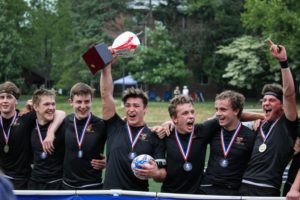

At Gregory the Great we not only learn about great warriors and the battles they waged on the pages of timeless literature, but we learn to become real literal warriors on our own fields of glory. Saint Gregory’s boys learn how to fight with their bodies and their hands. They learn how to take down a man charging at them full speed, a man who may be twice their size – this is no mean task. It requires a boy to summon that manly virtue called courage which always requires a willingness to perish in the fight. Last week we witnessed the Highlanders battle Saint Joseph’s Prep, holding their ground with confidence even when they were being severely beaten on the scoreboard at the half. In the second half, they came out roaring with a confidence born from their hard training in the snow and cold rains of Northeastern Pennsylvania.

The knowledge instilled into them during their many hours spent in this open-air classroom by the great coaches – van Beek, Snyman, Prezzia, and the brothers Kuplack finally paid off in full. They beat Saint Joseph’s Prep and then went on to defeat Cumberland Valley and win the Pennsylvania state rugby championship. That a school of 60 boys could accomplish such a victory might be the most unrealistic thing in the world. But with God, nothing is impossible. If we want to fight the good fight, to win the ultimate race, to be saints, we must get used to the unrealistic – to men fighting monsters and wars for women. It may well be the stuff dreams are made on, but it is the stuff of heaven.

In his book on Rhetoric, Aristotle calls his students to a fight even more noble than a physical fight. He says:

“It is absurd to hold that a man should be ashamed of inability to defend himself with his limbs, but not ashamed of an inability to defend himself with speech and reason; for the use of rational speech is more distinctive of a human being than the use of his limbs.”

Here Aristotle speaks of a kind of fight and struggle for the logos, the fight to understand, explain and defends one’s ideas in speech. Indeed, in the Ethics, Aristotle characterizes the effort to know as a kind of fight or struggle. He enjoins his readers to “strain every nerve” in their efforts to contemplate the highest truths. The attempt to come to the truth was once described by a Greek philosopher as an epic struggle: “a struggle for the whole.” This noble fight or struggle that our students begin to learn at Gregory the Great takes place not only in rhetoric class but in all of our classes. For in those very books mentioned before, we are learning not only that men must fight but also what men must fight for. We learn not merely that Odysseus must fight in order to return home, and must fight the suitors when he gets there, but we learn what it means to have a home and a faithful wife and what it means to be a good son even in the absence of one’s father. By passing with Odysseus through the many realms of inhuman or perversely human community, we learn what true human community is supposed to look like.

So what about Beowulf? Do we learn anything from him and from the unknown poet who gave us this tale? Yes, from Beowulf we learn that there are monsters we must fight and there may come a time when out of love for our people and our God, we may have to give our lives up in this fight. But one of the most practical and realistic truths we can learn from Beowulf became clearest to me after having several conversations with one of our seniors, Paul Reilly, who wrote his senior thesis on Beowulf. From Beowulf, we learn humility. Beowulf’s great strength was rooted in his constant knowledge that all of his gifts, all of his strength came from God, and that God was his source and protector.

Today we live in strange times – an age where the knowledge of the truth of man, of nature, and of God is very hard to see. We cannot go to the store and pick it up. It will not be found on a google search. No iPhone will ever lead us to it. No, this will require the long and hard effort of a lifetime. If we are to rediscover the truths of this forgotten realm – many of which are found in the books we read here, we must all become explorers, adventurers, and warriors like Beowulf, Odysseus, and Aeneas and we must be cheerful while we’re at it like Robin Hood and Roland. We will have to fight not only to understand these truths, not only to explain and defend these truths to others who do not understand or who attack them, but we must fight to live these truths ourselves.

So, my message today for our graduates is this: remember the crafts you have begun to learn on the rugby pitch, in the classroom, and in the chapel. Be bold enough to discover and listen well to wise men and wise books, be brave enough to struggle for the understanding of what you hear to be true and lovely and good, and to love it with all your heart. Be strong enough to live these truths in a world that is often arrayed against them, and to strive wisely and charitably to speak clearly and well to all you meet on the field of battle. For this battle, you will need only one thing: humility. The humility to understand that all good gifts, all power, all wisdom, all beauty, comes from God, the source of man’s good and of man’s strength to achieve it. And that, gentlemen, is why we read this stuff.