by Francisco Stender, Class of 2019 Valedictorian

Reverend Father, Faculty, Dormfathers, Families, Students, Friends,

My classmates and I are graduating from this Academy today, and even though I am still something of a boy, I hope I will not appear too presumptuous if I propose to tell you a secret about education. Do want to know what it is? It is one of the reasons why this school is a good school and why it raises good boys who, God willing, will be good men. It is something very important that we students do every morning, whether we like it or not. Here at Gregory the Great Academy, we begin every day by making our beds. That’s what I learned here after all these years. That’s it. But that’s not all.

Making your bed in the morning may seem like a simple chore, but if you look closely, you can see how important it really is. If you cannot complete this small task, how can you expect to perform greater ones in the future? The challenge to make your bed every morning means far more than getting your room passed in time to grab some breakfast before class. It is the challenge to perform one small act of discipline at the start of each day. It is about beginning well, and as I sat down to begin writing this speech, I thought a lot about all those times I made my bed in the cold pre-dawn darkness of the dorms. There are plenty of nursery sayings about “well begun is half done,” but what do things well-begun lead to? When all is done, where do they end? We have made our beds. What now must we lie in? There are other wisdoms of old men that say, “Your beginning is only as good as your end.” Now that our time here is over, I wonder how well we made our beds.

Though we are yet to see where our journey has brought us, I can clearly see the paths that have led me to this moment with all of you. My journey at Gregory the Great has been filled with many fond memories. I remember our class going on a weekend trip to Promised Land State Park with Mr. Strong. The trip was filled with fishing, swimming, hiding from the rain, stacking our hammocks on top of another, and so much more. When we left for the trip, none of us thought that it would turn out to be so fun. It changed us and brought us closer together. In a way, I never expected some of the best things that have happened to me and around me at this school. I never thought I would run six miles with Declan O’Reilly just to get hot chocolate mix (which we never found); or see Sebastian Adamowicz run around like a headless chicken and then jump into the water after he sat down on a yellow jacket nest. It is moments like these that I will never forget and will always cherish because they were happy moments that I spent with my friends doing good things in a good place.

What is really surprising, though, is to think that without my time here, I never would have experienced any of these things at all, things that are inseparable to me now. I never would have known these friends of mine who are now such a deep part of my life. In fact, if all of us went to the same school in some other place, I don’t think we would all be the same friends we are now. And I know for sure that we wouldn’t share such memories. In no other place would we be able to find them. This journey that we have all made is full of such surprises, but it is now come to an end. Even that is hard to believe.

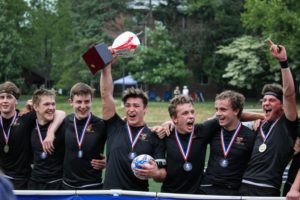

We have experienced many unforeseen joys and sorrows. Everybody’s lives suddenly changed when Fr. Christopher got sick, and none of us ever would have expected Peter Key to suffer such a terrible illness. We even had to say goodbye to some alumni who unexpectedly passed away this year. It has been a sad year, in many ways, but even with all these tragedies, our beloved school still thrives! We are about to complete another successful year here at Elmhurst and the school farm is taking off. Many of the old traditions are being revived, thanks to the help of the alumni staff members. This has also been the most successful athletic year in the school’s history. From our tenacious soccer team that dominated their way to the district title, to—as Mr. van Beek called it—the best defense in school history that allowed us to defeat our rival, Cumberland Valley, and win the state title.

As we prepare to part from each other’s company and from this school, I would like to take this opportunity to say a parting word to each of you, my classmates.

Sebastian Adamowicz, I hope you never forget the coffee morning fastbreaks or the number 73. I know you will go on to do great things, just like how you led us to a state title.

Paul Hebert, I know I will miss the random wall and hearing about your 5:30 am workout. I can’t wait to meet up in a couple of years after we have both joined the military.

Paul Reilly, how can I forget all the crazy Scandinavian folk songs you got stuck in my head? Or the time you were enraged because someone cooked bacon on your forge? Good luck at trade school and make some awesome knives.

Declan O’Reilly—oh, where to start? Between swimming across that river in France, or the room we shared this year, we have so many memories. But I know the experience we shared together as kitchen prefects cannot be matched and, for good or ill, will never be forgotten.

Peter Kelly, I will miss the fun we have shared and the mischief we have gotten into. I feel that it was yesterday when we were running from Jack Davis after jokingly telling him the seniors were buns. We showed him.

Nathan Bird, I hope you don’t forget that trip to Boston. I know I won’t. We went everywhere! That was the day I really got to know you and see how hilarious you are. Hopefully, someday I’ll get a chance to go shooting with you.

Joe Bell, you are one of the funniest people I know. I will never forget the time you wrote a very convincing Rhetoric speech on why our class deserved doughnuts—which we did.

Joe Landry, I remember the first time we went camping together and I was thinking, “Who is this crazy guy climbing up trees to set up a lean-to?” What’s funny is, you weren’t just climbing the branches; you actually were pulling yourself up inch by inch with a rope wrapped around the tree. I’ll miss you and thanks for being such a good prefect for my brother.

Michael Kaufman, from the first time I met you, I knew our time together was going to be a blast. I never will forget the time we bought $40 worth of senior food in coins; or when we tried to learn sign language so we could talk in class. I have to say, you are the only person I know who has gotten into trouble for reading too much. I can’t wait to hear about whatever crazy idea you get or contraption you build. You are probably the smartest person I know.

Aidan Hofbauer, we spent a lot of time working out during free time, even though most of it was just us talking. It makes me so happy that our dream to win states came true. We would always talk about winning and how if we could gain ten extra pounds, it might be enough to give us an edge over the other team. I can’t thank you enough for the motivation you gave me.

Aidan Gibbons, I will never forget all the time we spent as roommates. They may be the fondest memories I have. Ever since the first week we spent together in soccer camp, you have been one of my best friends. We have had some good adventures, from almost making our way into Trump Hotel, to camping out in the biggest blizzard in years, to our haunted barn room that we had so many ideas for, but none of them worked.

My classmates, you have made my time at Gregory the Great Academy wonderful. I say these things not as some final farewell that you might hear at a funeral, but rather as a farewell at the completion of a journey. Shakespeare wrote, “Journeys end in lovers meeting, every wise man’s son doth know.” Our journey is ended, and I love you all. In a few moments, when we receive our diplomas, our lives will be forever changed. We will no longer be students, but alumni. Our time at Gregory the Great has come to an end, and I can proudly say that there is no other group of guys that I would have desired to make this journey with. We will always be friends, and a part of us will never leave this school behind.

To my fellow students, especially my brother, Jude, I say, no matter how hard it gets or how unpleasant the moment may seem, always remember the good things you’ve done at Gregory the Great Academy, and the students who went before you. You have been tasked with keeping the tradition and culture of this school alive, so do it with pride. Even when you’re sitting in a freezing cold ice bath or waking up at 7am after a late banquet, never forget the task you have been given. You are on a journey, as we were, and it is up to you not to lose your way and remain true to the course. Make your beds every morning and make them well.

The journey that Gregory the Great Academy is is no easy journey, but it is one that rings with the laughter of friends. It is full of excitement, new people, trials, and triumphs, but what is most important is that Gregory the Great Academy challenges us to live life to its fullest for the greater glory of God. Our life is full of journeys and the journey’s call, but it is up to us to embark on them or not. If we choose to undertake the journey, and choose to do so every morning, willing to rise to the occasion, to give our all, the things we will learn and the things we will remember will be unparalleled. The journey of every St. Gregory’s boy begins with making his bed and it ends with a hard-fought goal reached. Even a little thing like making your bed can be, must be, the start of something great.

Thank you.