by Sean Fitzpatrick

One of the tragic results of the triple choke-hold demagoguery, diversity, and the almighty dollar have on the American classroom is that teaching is becoming less of an interpersonal art and more of an impersonal programming session. Teachers can certainly combat, and hopefully reverse, this crisis by offering students the truth of their subjects through the truth of who they are as teachers—when they teach themselves.

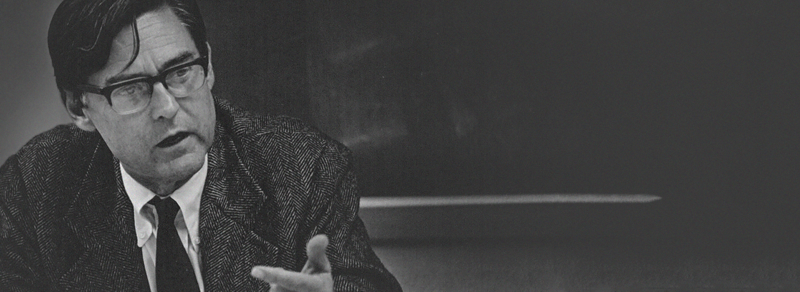

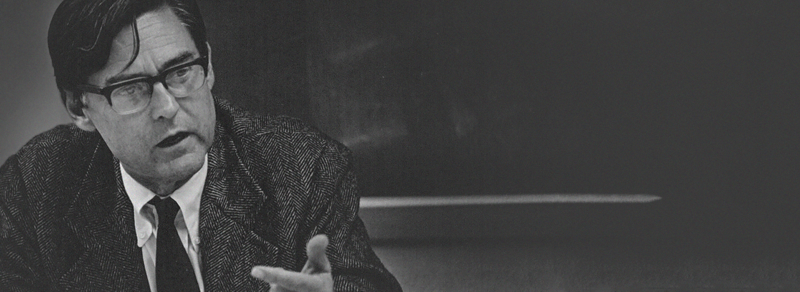

G. K. Chesterton once said with honest irony, “Education is the period during which you are being instructed by somebody you do not know, about something you do not want to know,” which is precisely what education should not be. Denouncing those who systematize and stagnate education in this way, Catholic professor John Senior wrote in his unpublished work, The Restoration of Innocence: An Idea of a School:

They often say derisively, ‘He teaches himself instead of the subject.’ But he is the subject. If there is reason for derision it isn’t such teaching but the failure (usually the vanity) of the teacher. Every teacher teaches himself. And every student studies himself. Leonardo da Vinci said Narcissus contemplating the reflection of his own beauty in the mirror of a pool was the perfect artist—the perfect student, too, who sees in the mirror of language and nature a reflection of himself, discovering himself through what he thinks and feels. The anesthetic boy reflecting what the teacher says, rather than his own sensitive, emotional, volitional and intellectual experience, is as vain as the actor-teacher putting on an empty show.

If teachers are to teach effectively, they must, as Senior put it, teach themselves. It is a well-worn adage that teachers can only give what they have, and what they have most intimately are their own selves. No power-point presentation can come close to the power of a person willing to reveal his life and loves in the context of a subject he is passionate about. With such teachers—and many have had them and remember them best—students advance with eagerness and energy towards their individual perfection, discovering themselves through a teacher’s sharing of himself. In this approach, the importance of personal experiences that augment and enliven the subject matter to create human connections cannot be emphasized enough.

Education is an encounter and engagement with things good, true, and beautiful in the context of natural human interactions for the sake of human happiness. As an action exercised by one human being upon and with another, education has far more to do with friendship and faith than with career-oriented, politically correct lesson plans and talking points. Education can never be automated or prepackaged. It requires a dynamic relationship, and relationships require human presence and dynamics, together with an open heart, an open mind, a good will, a knowledge of things, and facility in conversation.

Subjects and academic rigors there must be, of course, but the mode of approach is central to any meaningful education. In following the ordinary principles of human interaction, teachers can be extraordinary educators, and the same can be said for students—especially once both come to the realization that they must teach and learn universal truths through their particular perspectives. For example, students of C. S. Lewis’ The Four Loves will be far keener and more disposed to learn hearing how their teacher fell in love than with the text alone. Teachers must be personal if they intend to teach people. Human beings find other human beings interesting, and teachers must be human when they teach if they are to form human beings. Furthermore, as Senior says, teachers should draw their students towards the material as people themselves, not as programs following a closed system, urging them to reflect inwardly and speak outwardly.

True education is more than the mere memorization of information or the assimilation of facts. It is a cultivation of soul that, as St. John Henry Newman says in his Idea of a University, “implies an action upon our mental nature, and the formation of a character.” The formation of character implies an active character, and that character, that subject, again as Senior posits, is the teacher and the student. The more honest a teacher is about who he is, the more honest will his students become, beholding who they themselves are in the shared light of their educator who leads them joyfully, as a flesh-and-blood person, out of the cave of shadows. Teachers who teach themselves so that students can learn who they are and through who they are establish an atmosphere of friendliness and mutual understanding—they establish rapport.

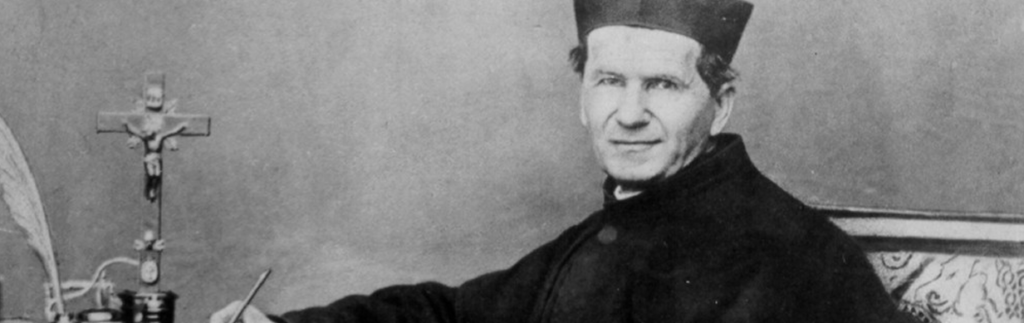

Rapport is the relationship championed by St. John Bosco wherein mutual trust and respect is nurtured in a spirit of friendship, sympathy, and cooperation. The teacher who is actually and clearly interested in helping people become better and more fulfilled will win the hearts of students. Rapport arises when this human understanding between them takes shape: that the teacher sincerely cares about the welfare of the student and the student appreciates this and acts accordingly. When rapport is established, a teacher can become a positive influence as a person upon people, and the students will strive to please those whom they love, for love is the beginning and end of rapport. And love, as Christ taught His friends, is impossible without a human connection.

Education will not be humanized until teachers and students alike first recognize that the realities they teach and learn are offered and received through themselves in an atmosphere of rapport. They should freely teach and learn the eternal truths through their own personal observations, experiences, perspectives, studies, thoughts, and queries. They should enjoy the material together as friends, talking about what they think, observe, like, and do not like. They should allow ideas to intermingle with stories instead of scripts. Conversations do not have plans. Neither do dynamic, interpersonal relationships which bring about perfection in the educational arena; namely, the perfection of a person at the hands of another person, a teacher, who is not afraid to teach himself.